I have just spent an inspiring couple of days at the St Hilda’s Crime Weekend. Listening to writers talking, among many other things, about the books they grew up with and that had influenced their own work made me wonder what my life would look like, and who I’d be, if I’d never read any books.

First of all, what else would I have done with all that time? I often had many solitary childhood hours to fill on holidays and weekends in a small village in the Eden Valley. I was happy to read any book that came to hand (I still have the compendium volumes of John Buchan and Leslie Charteris). Otherwise, in pursuit of the most obviously active element in the landscape, I went bird-watching. There wasn’t a lot else to do. I’m not musical and can’t draw. It was only on occasional sufferance that girls were allowed to join in the cricket played on the village green. I could have played more Patience, or sewed or cooked or picked and helped my mother bottle more soft fruit, or taken even longer walks on the fells, but where would I have gone in my mind?

My sense of who my parents and older brothers were was informed by picking up and reading the books they put down. If ever I whined that I was bored, I was told to read a book. Dad liked historical biography and crime fiction. The younger of my two brothers was into 1960s sci-fi and P.G. Wodehouse. While I was ten and eleven, my eldest brother was studying ‘A’ Level English. Desperate to impress him, I struggled to understand Gerard Manley Hopkins and D.H. Lawrence. Most of it went over my head, but the mystery and richness of their language made me long to understand what sort of thinking they were doing when they wrote like that. (My eldest brother remained unimpressed.)

My mother was only an occasional reader, but I first came across the word ‘homosexual’ on the back cover of a Muriel Spark novel she was reading in a hotel room on a trip to London. I was, again, probably aged about ten, so this was before decriminalisation in 1967 and I had to nag her a bit to explain what the word meant, which was itself unusual. I think I tried reading a chapter or two of the novel and didn’t find it terribly interesting, but, because my mother’s taste in fiction was influenced by literary reviews in Sunday newspapers (this was when colour supplements were still new and exciting), I grew up benignly associating the word ‘homosexual’ with a grown-up urban world that seemed chic and smart.

Choosing my own books either on fortnightly visits to the library with my Dad, or spending birthday and Christmas book tokens, became a way to strike out for independence, and so I would deliberately select books none of my family would be likely to read.

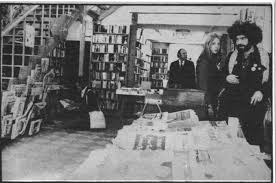

There are certain authors (Georgette Heyer!) I will forever associate with certain friends. It was a young man I rather liked at university who encouraged me to read widely across nineteenth-century Russian literature. Anything I have ever learnt since about Russian landscape, art or politics is inevitably coloured by that rather intense period of reading. During the Nixon era, thanks to another boyfriend, I discovered the long-gone Compendium Bookshop in Camden which offered a subversive range of contemporary American writing that has helped prepare me for the current administration.

And on and on, until I cannot conceive of who I could possibly be without all the books I’ve read. And even if I could somehow subtract them from my head, I can’t imagine what would have taken their place, not only to fill the time but also to create an alternate understanding of the world and its history, geography, politics, people, relationships and emotions. I certainly can’t believe that I would ever have become a writer of fiction. I suspect I would have branched out from bird-watching and become a naturalist. And then written about that.